Researchers at the Whitaker Institute in NUI Galway have found that Donegal County Council has been underfunded, and would be receive more under a new Revenue Equalisation Model they are proposing.

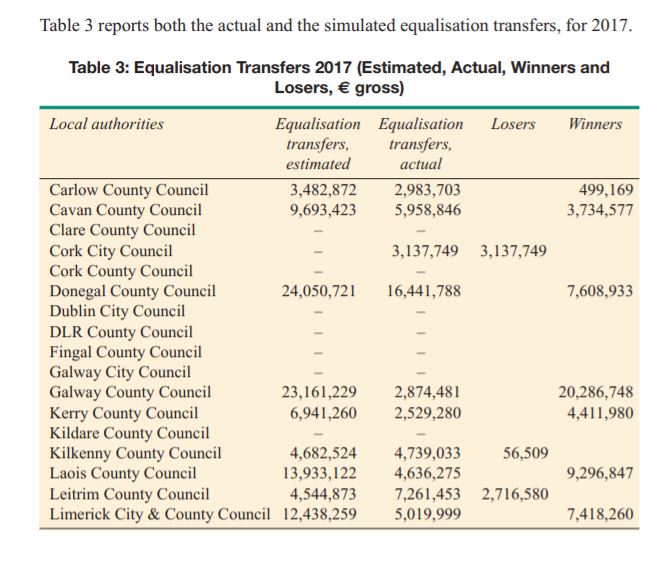

An analysis of 2017 figures shows Donegal County Council to have the fifth highest deficit in the country.

Of the 31 local authorities, 20 are already in receipt of such payments, totalling €133.5 million for the year 2021. The local authorities that currently receive the biggest grants in euro terms are Tipperary, Donegal, and Mayo County Councils, and Waterford City and County Council.

In their report, the research team say in other local government systems internationally, the equalisation transfers are based on a well-designed formula, objective and quantifiable data and estimates of fiscal capacity.

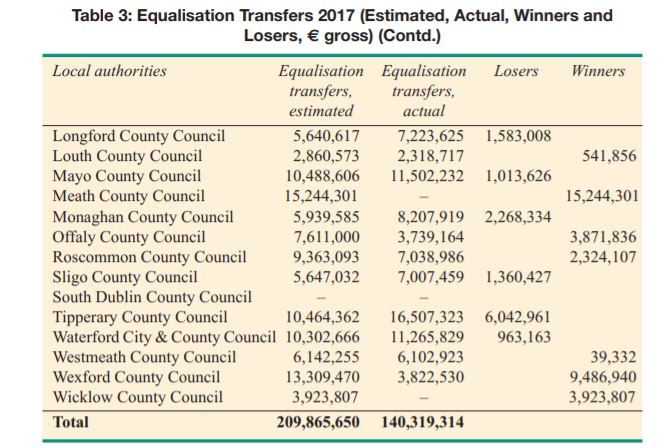

In the study’s simulations, the local authorities that receive the largest grants are Donegal, Galway, Meath, Laois, and Wexford County Councils.

An analysis of 2017 figures in the report shows that Donegal had a shortfall of almost €7,610,000, or €48 for every person in the county.

Wednesday, 28 April, 2021: Researchers at the Whitaker Institute in NUI Galway have developed a new methodology for estimating top-up grants for local councils with insufficient revenue bases. The research has been published in the 2021 Spring issue of The Economic and Social Review, Ireland’s leading journal for economics and applied social science.

Stephen McNena co-author of the report from the J.E. Cairnes School of Business and Economics, NUI Galway, explains: “Currently, these so-called equalisation grants are funded primarily from the 20 percent of Local Property Tax receipts that are pooled and redistributed as additional payments to councils with smaller revenue bases, with the allocation based on historical baseline supports. Of the 31 local authorities, 20 are in receipt of these payments, totalling €133.5 million for the year 2021. The local authorities that currently receive the biggest grants in euro terms are Tipperary, Donegal, and Mayo County Councils, and Waterford City and County Council.”

Under the revenue equalisation model proposed by the authors, as is common in other local government systems internationally, the equalisation transfers are based on a well-designed formula, objective and quantifiable data and estimates of fiscal capacity. Regarded as the ‘most sophisticated technique for assessing interjurisdictional differences, and designing an equalisation transfer system’, fiscal or revenue-raising capacity is the potential ability of a local government to raise own-source revenues.

In the Irish case, own-source or local revenues are raised through commercial rates, the Local Property Tax, and fees and charges for goods and services. Estimates of fiscal capacity for the 31 local councils are calculated, and compared to a standard defined as the national average of the fiscal capacity estimates. Where the fiscal capacity of a local council is less than the standard, a local council receives an equalisation payment equal to this shortfall.

In the new model, 22 local authorities are eligible for equalisation grants, totalling almost €210 million with the funding now derived from central government. In this study’s simulations, the local authorities that receive the largest grants are Donegal, Galway, Meath, Laois, and Wexford County Councils.

Given the highly political nature of fiscal equalisation, any new redistributive scheme will inevitably result in losers and winners. Per head of the population served, the study found that the biggest winners are Galway, Laois, Meath and Wexford County Councils. Given that the Local Property Tax will no longer be used to fund these equalisation payments under this new model, urban councils also win out with an additional €40 million revenue income available annually to the four Dublin local authorities to fund essential services for their residents.

Dr Gerard Turley, co-author of the study from the J.E. Cairnes School of Business and Economics, NUI Galway, concludes: “As for the sensitive issue of the losers, alternative sources of funding include, if the fiscal space allows, higher taxes locally levied on commercial and/or residential properties, or in cases where it is deemed necessary, a temporary transition payment from central government. Either way, our new model provides for a local government funding model that is more transparent, sustainable and, most importantly from the perspective of financially weaker local councils providing comparable levels of public services, equitable.”

The authors manage the local government finance website www.localauthorityfinances.com

To read the full paper entitled ‘Equalisation transfers and local fiscal capacity: A new methodology for Ireland’ visit: www.esr.ie or https://www.esr.ie/article/